BETHGE, Dietrich (#290)

#290

Dictrich BETHGE

Resistance

Alan Pollock’s Rough Notes:

A work in progress – the fuller biographies will emerge in due course: please sign up to the Newsletter (bottom of the page) and we’ll let you know when we’ve done more justice in writing up our extraordinary signatories.

Dictrich BETHGE, godson of and christened by the renowned German theologian Dietrich BONHOEFFER, was chosen to represent the opposition and GERMAN RESISTANCE MOVEMENTS against Nazism, which too often would be forgotten during and after the war. Post-war many Christians have been engaged in the process of re-examining the role of the Church in Germany during the Nazi era. What has become evident in this undertaking was the depth between the ideals the Church had always set for itself and the way it responded to the brutalization of the German government under Adolf Hitler.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was one of the few church leaders who stood in courageous opposition to the Fuehrer and his policies. The Protestant Pastor Bonhoeffer had links with British churches pre-war during the rise of Nazism and after the Hitler Plot until his death in the FLOSSENBURG concentration camp in 1945 and shortly before the war ended. His view of Christianity’s role in the secular world has become very influential Disheartened by the German Church’s complacency with the Nazi regime, 27-year-old Bonhoeffer accepted in the autumn of 1933 a two-year appointment as a pastor of two German-speaking Protestant churches in London, St. Paul’s and Sydenham. He explained to Barth that he found little support for his views, even among friends, and that “it was about time to go for a while into the desert”, but Barth regarded this as running away from the real battle. He sharply rebuked Bonhoeffer that “I can only reply to all the reasons and excuses which you put forward: ‘And what of the German Church?'” Barth accused him of abandoning his post and wasting his “splendid theological armoury” while “the house of your church is on fire” and chided him to return to Berlin “by the next ship.” Bonhoeffer however did not go to England simply to avoid trouble at home but hoped to use the ecumenical movement in the interest of the Confessing Church, running up staggeringly high telephone bills to maintain his contact with Niemöller. In the international gatherings, he rallied people to an opposition to German Christian movement and its attempt to amalgamate Nazi racism with the Christian gospel.

On April 6, 1943, Bonhoeffer and Dohnanyi were arrested not because of their conspiracy but because of long-standing rivalry between the SS and Abwehr for intelligence after a note that discussed plans for a journey by Bonhoeffer to Rome, where he would explain to church leaders why the assassination attempts on Hitler in March 1943 had failed. Bonhoeffer’s involvement in assassination plots was not known by the Gestapo as the Abwehr succeeded in explaining away the most damning documents as official coded Military Intelligence materials. Dohnanyi and Bonhoeffer were suspected of subverting Nazi policy toward Jews and misusing the Abwehr. Bonhoeffer was, for instance, suspected of evading military call-up, using the Abwehr to circumvent a Gestapo injunction against public speaking and staying in Berlin. After the failure of the July 20 Plot on Hitler’s life in 1944 and the discovery of secret Abwehr documents relating to the conspiracy by the Gestapo in September 1944, Bonhoeffer’s connections with the conspirators were discovered.

He was transferred from the military prison in Berlin Tegel, where he had been held for 18 months, to the detention cellar of the house prison of the Reich Security Head Office, the Gestapo’s high security prison. In February 1945 he was secretly moved to Buchenwald concentration camp, and finally to Flossenbürg. On April 4, 1945, the diaries of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of Abwehr, were discovered and in a rage upon reading them Hitler ordered that the Abwehr conspirators be destroyed. Bonhoeffer was led away just as he concluded his final Sunday service and asked an English prisoner Payne Best to remember him to Bishop George Bell of Chichester if he should ever reach his home: “This is the end — for me the beginning of life.”

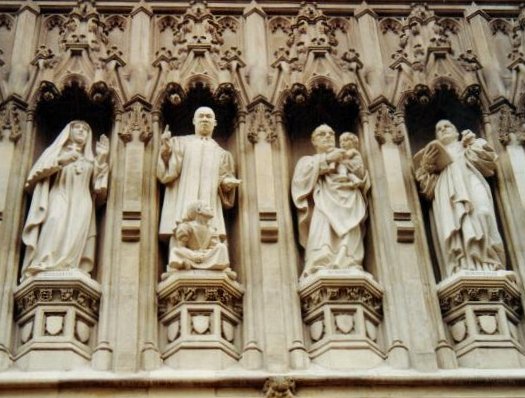

Gallery of 20th Century Martyrs at Westminster Abbey. From left, Mother Elizabeth of Russia, Martin Luther King, Oscar Romero and Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Bonhoeffer is commemorated as a theologian and martyr by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the Church of England and the Church in Wales. His life as a pastor and theologian of great intellect and spirituality, who lived as he preached and his martyrdom in opposition to Nazism, exerted great influence and inspiration for Christians across broad denominations and ideologies including figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Archbishop Desmond Tutu.