A Nazi admirer (who later became a communist), he had met Adolf Hitler in pre-war Germany. He struck Hitler as a pleasant young man (“he could always tell an Englishman from an American,” Burn noted) and the Führer invited him to Nuremberg to witness the Nazi rallies of September 1935, all expenses paid. Hitler signed Burn’s copy of his autobiography Mein Kampf, but “it fell through a hole in my car the same day and I never saw it again”.

BURN, Michael C (#86)

#86

Michael Clive "Micky" Burn, MC

British Army

11 December 1912 – 3 September 2010

“I saved her life in the war… and later she became ‘Audrey Hepburn'”

“Michael Burn was one of the last survivors of the naval commando raid on St Nazaire, after which he was captured and imprisoned at Colditz.

Michael Burn (left) captured, indicating the success of the raid with his fingers

Burn was one of many young British men of the 1930s attracted to the showmanship of the Nazis. From Germany he wrote home: “It is so wonderful what Hitler has brought this country back to.” He was “stunned and excited” by the cohesion of Germany after the political disarray in Britain. Then there was the theatre of Nuremberg: “great lights in the sky, moving music, the rhetoric, the presentation, timing, performance, soundtrack, exultation, and climax. It was almost aimed at the sexual parts of one’s consciousness.”

But such enthusiasm for the Nazis turned to disenchantment after a day trip to Dachau, the first of the concentration camps. Burn joined the Army as a part-timer in 1937 and, when war came and his Territorial unit was reconfigured into a Special Service Brigade, captained No 6 troop of No 2 Commando.

In March 1942 this unit took part in the assault on St Nazaire, the fortified port on the French Atlantic coast. The mission – to deny its use to the biggest German battleship, Tirpitz – was characterised by Burn’s commanding officer as “the sauciest job since Drake”.

St Nazaire: HMS Campbelltown resting on the wall it would soon destroy

The mission – to deny its use to the biggest German battleship, Tirpitz – was characterised by Burn’s commanding officer as “the sauciest job since Drake”.

The audacious plan called for 24 small groups of commandos to man a destroyer, Campbeltown, loaded with explosives on delayed charges, which would ram the dock and later blow herself up, taking the outer caisson with her. On impact, the soldiers were to leap ashore and blow up German gun towers and other installations.

But the approaching British force was detected and fixed in the beams of enemy searchlights, and Burn heard the whistling of German tracer fire just before he jumped from his motor-launch and scrambled up on to a long jetty.

As he ran for cover, he was wounded by fire from a German gun emplacement. Hearing that Campbeltown had successfully rammed the outer caisson he prepared to re-embark when he was captured by three Germans who debated whether to kill him. When an English voice challenged them, they ran off, and Burn, with an Irish rifleman called Paddy Bushe, managed to get aboard a ship moored in the estuary, only to be arrested by an armed German patrol.

Seeing that he was being photographed for propaganda purposes, Burn formed his fingers of his left hand into a V-sign as they were marched away. He was interrogated by a German team that included Hitler’s personal interpreter, whom Burn recognised from Nuremberg in 1935. During the questioning, there was an explosion as Campbeltown‘s payload detonated as planned.

Five men were eventually awarded the VC for their parts in the St Nazaire raid, which Mountbatten described as the “grand story of the war”. Burn was the sole survivor of his unit.

Burn recorded the moment, as the windows in the interrogation-room were blown in. “Not only had she exploded,” he later wrote, “but taken with her scores of German investigators, sightseers and souvenir-hunters.” Tirpitz never ventured out into the Atlantic, and the dock remained out of action until after the war. Five men were eventually awarded the VC for their parts in the St Nazaire raid, which Mountbatten described as the “grand story of the war”. Burn later realised that he had been the sole survivor of his unit.

Imprisoned in a concentration camp, he was surprised to receive a Red Cross parcel, no donor being indicated. This turned out to be from Ella van Heemstra, mother of the future actress Audrey Hepburn, whom Burn had briefly met in England in 1939 when she had been a lanky girl of 10. Her mother had seen a German newsreel showing Burn flashing a V-sign while being marched into captivity and later, with the help of the cinema owner, removed the frames in question before splicing the film back together. With the blown-up picture of Burn, Ella van Heemstra contacted the Red Cross, which dispatched the parcel.

Young Audrey Hepburn (1938), whose mother sent Micky Burn a Red Cross parcel having seen a clip of him in a newsreel.

Having been held in solitary confinement in a series of Oflags – and after refusing an offer to become a German stool-pigeon in a “special” camp – Burn was moved in August 1943 to Colditz, where he spent the remainder of the war. His politics had lurched to the Left, and his fellow British captives, as well as the Germans, regarded him as pro-communist. Meanwhile he was given the job of transcribing news gleaned from a secret wireless set, which included reports of the D-Day landings, the crossing of the Rhine, and approach of the Americans. He also wrote a novel, Yes, Farewell, and studied for (and was awarded) an Oxford degree in Social Sciences. On his liberation in April 1945 Burn was awarded the Military Cross.

“Michael Burn, who has died aged 97, had a life strewn with risks, setbacks, disenchantments and deceptions, and illumined by love affairs, literary acclaim and marvellous friendships. Man about town, journalist, soldier, poet, novelist and playwright, and latterly a breeder of mussels on the Dwyryd and Glaslyn estuaries of north-west Wales, Burn – widely known as Micky – lived his life with panache and a debonair grin. This he maintained whatever befell him, whether incarceration in Colditz as a PoW or in reporting the communist show trials of postwar Europe. There were contradictions in his character, flaws and conflicts even, which he wrote about with self-knowledge.” Obituary, The Guardian

Immediately afterwards he helped save Audrey Hepburn’s life, by sending food parcels to her in occupied Holland where she was critically ill in hospital, and where she and her mother were subsisting on tulip bulbs. Burn also sent them hundreds of cartons of cigarettes, which commanded high prices on the black market. The money raised from their sale bought Audrey Hepburn supplies of the new drug penicillin, which were crucial in her recovery from an infection brought on by malnutrition.

Audrey Hepburn (1956) having recovered from life-threatening malnutrition with the help of Micky Burn [Signatory #86]. Later in life, she devoted much of her time to UNICEF.

In the week of March 1946 in which Churchill first described an Iron Curtain descending across Europe, Burn was posted to Vienna as a correspondent for The Times. There he saw his Colditz book hailed as the “war’s greatest novel” by the Daily Worker. The following year The Times moved him and his new wife to Budapest to be the paper’s Balkans correspondent.

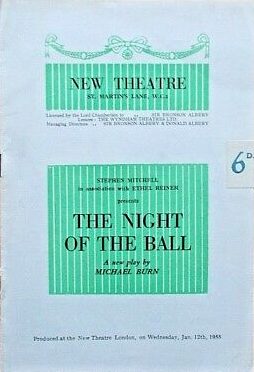

The Night of the Ball by Micky Burn theatre programme

Returning to London in the early 1950s, he wrote a play, The Night of the Ball, which opened in the West End in 1954 starring Gladys Cooper. Though married, Burn had long been aware of his homosexuality, and on his return from Hungary “the old urge” had returned. During a homosexual assignation in Bayswater with a youth, Burn was detained by two “detectives”, who demanded £70 to settle matters “privately”. The blackmailers were arrested and sentenced to prison, but Burn’s identity remained protected under law, and although the case made the News of the World, he was referred to only as “Mr X”. Soon afterwards Burn left London and spent the rest of his life in an eclectic and bohemian house on the Portmeirion estate in north Wales designed by the architect Clough Williams-Ellis.

Michael Clive Burn was born in Mayfair on December 11 1912, the elder son of Sir Clive Burn, KCVO, an Oxford cricket blue, steeplechaser and solicitor. At birth, Michael’s father tricked out the child’s cot with his racing colours and put him down for membership of MCC (the boy later turned it down, to his father’s dismay).

He was brought up in Hyde Park Square, Bayswater. Later, when his father was appointed secretary to the Duchy of Cornwall, the family moved to a grace-and-favour white stucco house in Queen’s Gate, diagonally opposite Buckingham Palace. From their nursery window, Michael and his siblings used air rifles to take pot shots at Britain’s first Belisha beacon, situated next door.

After being dispatched to Winchester, Michael confided to his father that he might be homosexual, only to be sent to see George V’s doctor at the Palace, who gave him benzedrine injections which made him hyperactive. Burn was then referred to a Harley Street specialist. After a cursory physical examination, the young man was pronounced “normal”. From Winchester he won a Classics scholarship to Oxford (an achievement he learned on opening The Times while waiting for a train on Winchester station) and spent what he later called a “disgraceful” year at New College.

In the 1931 vacation, Burn stayed at a rented villa at Le Touquet, where his maternal grandfather had built the first hotel and casino, turning it into a fashionable resort. There he was drawn into the social circle of Syrie Maugham (divorced from her novelist husband Somerset Maugham) and introduced to the motor-racing ace Tim Birkin (later Sir Henry Birkin, Bt). Realising that he had done no work nor any of the reading expected of a scholar, Burn decided not to return to Oxford and instead agreed to ghost Birkin’s autobiography, published as Full Throttle (1932).

Full Throttle, for which Burn was the ghostwriter.

Although Burn knew little about cars, and next to nothing about motor-racing, the book sold well, and led to him being commissioned to write the history of Brooklands, which appeared as Wheels Take Wings (1933). During his research, he met a student from Trinity College, Cambridge, called Guy Burgess. Two years older than he was, Burgess was openly homosexual, a Marxist, and (according to Burn) “the most stimulating talker I had so far met”.

He was also later to become a member of the Cambridge spy ring and a defector to Moscow. He introduced Burn to other members of his louche Cambridge set, and took him to lunch with EM Forster.

Wheels Take Wings by Michael Burn

Without informing his parents of his whereabouts, Burn drifted to Germany, rented a tiny flat in Munich at a mark a day, and mingled with sundry Oxbridge graduates training for the Diplomatic Service, including Donald Maclean, Burgess’s fellow future-spy and fugitive to Moscow. Moving on to Italy, Burn was a guest of Alice Keppel, Edward VII’s mistress, and her daughter, Violet Trefusis, at Mrs Keppel’s palatial villa in Florence.

On his return to London, Burn enrolled at the Pitman college and divided his time between his parents’ house and that of Viola Tree, the actress and daughter of Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, the Edwardian actor-manager. Burn helped Viola Tree to edit the memoirs of her husband Alan Parsons, who had died of pneumonia in 1933.

Having learned shorthand and typing, in 1934 he was taken on as a reporter by the Gloucester Citizen, an evening newspaper whose editor gave him a trial at £3 a week. Burn, then 21, stayed for two years, spending his summer holiday in 1935 in Munich. One of his contacts there was Unity Mitford, an admirer and confidante of Hitler, whom he had known since attending a party at the Mitfords’ house in Rutland Gate during her year as a debutante.

“People think she is going to marry Hitler,” Burn reported. Taking tea with her at the Carlton tea rooms, Munich, Burn was struck by Unity Mitford’s extreme reaction when the Führer himself appeared. She trembled. “Hitler passed our table and spoke to her,” Burn recalled, “and then he went on to his table in the garden. One of his adjutants came back and said Hitler had invited her to join them. She rushed off after him. I might not have existed.”

Burn sent a wire to his editor in Gloucester, explaining that his return would be delayed. After a row with Unity Mitford, he never saw her again. The editor wrote Burn a letter of recommendation to The Times, whose editor, Geoffrey Dawson, gave him a job and assigned him to coverage of the blossoming affair between the new King, Edward VIII, and Mrs Simpson.

Although at this stage the romance had remained unreported by the British press, Burn was particularly well placed to furnish details, his father having been appointed secretary, solicitor and keeper of the archives to the Duchy of Cornwall. Burn père‘s friend, Walter Monckton, was not only a member of the Duchy council but also the King’s go-between with the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin.

In February 1938 Burn was commissioned into the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, and the following September accompanied Dawson to London Airport in The Times’ s Rolls-Royce to see off the new prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, en route to Munich to meet Hitler. The following summer Burn was in Canada and the United States to cover the visit of the new King and Queen, and when war was declared in September, joined his Territorial battalion and took part in guerrilla actions in German-occupied Norway before joining the St Nazaire raid.

In the 1950s Burn published five volumes of poetry and two further novels. In the 1960s he ran on communist principles a mussel-farming co-operative in north Wales, a venture that proved financially disastrous as he insisted on turning all the profits over to his workers.

His autobiography, Turned Towards the Sun, appeared in 2003.

Michael Burn married, in 1947, Mary Booker (née Walter), whose first great love had been the badly-burned wartime pilot Richard Hillary, who recovered sufficiently to fly again but died in a crash in 1943. In 1988 Burn produced Mary and Richard, a moving account of their story based on the couple’s love letters. After her death in 1974 he confessed to two homosexual coups de foudre. There were no children.” (Obituary courtesy of The Daily Telegraph)

Micky Burn in Wales in 2009 near his home filming his documentary “Turned Towards the Sun”

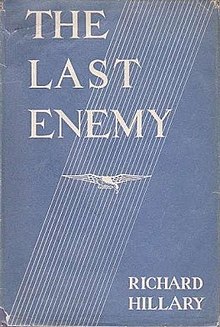

‘Mary and Richard’ by Michael Burn & ‘The Last Enemy’ by Richard Hillary

Mary and Richard by Michael Burn

Recounts the intense, year-long love affair between World War II British hero Richard Hillary and the captivating, older Mary Booker until his death in a plane crash in 1943, as told by Booker’s husband of more than twenty years, Michael Burn. Hillary wrote The Last Enemy, an account of his experiences in the Battle of Britain. Hillary wrote about his first experience in a Supermarine Spitfire in The Last Enemy. (NB ‘Killy’ Kilmartin is Signatory #35]

The Spitfires stood in two lines outside ‘A’ Flight pilots’ room. The dull grey-brown of the camouflage could not conceal the clear-cut beauty, the wicked simplicity of their lines. I hooked up my parachute and climbed awkwardly into the low cockpit. I noticed how small was my field of vision. Kilmartin swung himself on to a wing and started to run through the instruments. I was conscious of his voice, but heard nothing of what he said. I was to fly a Spitfire. It was what I had most wanted through all the long dreary months of training. If I could fly a Spitfire, it would be worth it. Well, I was about to achieve my ambition and felt nothing. I was numb, neither exhilarated nor scared. I noticed the white enamel undercarriage handle. “Like a lavatory plug,” I thought. Kilmartin had said, “See if you can make her talk.” That meant the whole bag of tricks, and I wanted ample room for mistakes and possible blacking-out. With one or two very sharp movements on the stick I blacked myself out for a few seconds, but the machine was sweeter to handle than any other that I had flown. I put it through every manoeuvre that I knew of and it responded beautifully. I ended with two flick rolls and turned back for home. I was filled with a sudden exhilarating confidence. I could fly a Spitfire; in any position I was its master. It remained to be seen whether I could fight in one.

The Last Enemy by Richard Hillary (First Edition). In the preface for the book’s first edition in 1942 J.B. Priestley wrote: ‘The Last Enemy differs from all other books about the R.A.F. because its author, Richard Hillary, is by temperament and inclination, and to some extent training, a writer. … The value of this book lies in the fact that it is a statement of a fully articulate young man about life in a Service which is generally inarticulate. Richard Hillary happens to be a young man who doesn’t often find his way into the R.A.F. He is in my view a born writer.’

On 3 September 1940 he had just made his fifth “kill” when he was shot down by a Messerschmitt Bf 109 flown by Hauptmann Helmuth Bode of II./JG 26:

I was peering anxiously ahead, for the controller had given us warning of at least fifty enemy fighters approaching very high. When we did first sight them, nobody shouted, as I think we all saw them at the same moment. They must have been 500 to 1,000 feet above us and coming straight on like a swarm of locusts. I remember cursing and going automatically into line astern; the next moment we were in among them and it was each man for himself. As soon as they saw us they spread out and dived, and the next ten minutes was a blur of twisting machines and tracer bullets. One Messerschmitt went down in a sheet of flame on my right, and a Spitfire hurtled past in a half-roll; I was weaving and turning in a desperate attempt to gain height, with the machine practically hanging on the airscrew. Then, just below me and to my left, I saw what I had been praying for – a Messerschmitt climbing and away from the sun. I closed in to 200 yards, and from slightly to one side gave him a two-second burst: fabric ripped off the wing and black smoke poured from the engine, but he did not go down. Like a fool, I did not break away, but put in another three-second burst. Red flames shot upwards and he spiralled out of sight. At that moment, I felt a terrific explosion which knocked the control stick from my hand, and the whole machine quivered like a stricken animal. In a second, the cockpit was a mass of flames: instinctively, I reached up to open the hood. It would not move. I tore off my straps and managed to force it back; but this took time, and when I dropped back into the seat and reached for the stick in an effort to turn the plane on its back, the heat was so intense that I could feel myself going. I remember a second of sharp agony, remember thinking “So this is it!” and putting both hands to my eyes. Then I passed out.

Unable to bail out of the flaming aircraft immediately, Hillary sustained extensive burns to his face and hands. Before it crashed he fell out of the stricken Spitfire unconscious. Regaining his senses whilst falling through space, he deployed a parachute and landed in the North Sea, where he was subsequently rescued by lifeboat Lord Southborough (ON 688) from the Margate Station.

Hillary was taken for medical treatment to the Royal Masonic Hospital, Hammersmith, London; and afterwards, under the direction of the surgeon Archibald McIndoe, to the Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead, in Sussex. He endured three months of repeated surgery in an attempt to repair the damage to his hands and face, and went on to become one of the best known members of McIndoe’s “Guinea Pig Club” [See Signatory #32, Harold ‘Birdie’ Bird-Wilson, who was the second member of the Club]. He wrote an account of his experiences, published in 1942 under the title Falling Through Space in the United States, and as The Last Enemy in Great Britain.

Gradually I realized what had happened. My face and hands had been scrubbed and then sprayed with tannic acid. […] My arms were propped up in front of me, the fingers extended like witches’ claws, and my body was hung loosely on straps just clear of the bed.

Shortly after my arrival at the Masonic the Royal Air Force plastic surgeon, A. H. McIndoe, had come to see me. […] Of medium height, he was thick-set and the line of his jaw was square. Behind his horn-rimmed spectacles a pair of tired friendly eyes regarded me speculatively.

“Well,” he said, “you certainly made a thorough job of it, didn’t you?” He started to undo the dressings on my hands and I noticed his fingers – blunt, captive, incisive. By now all the tannic had been removed from my face and hands. He took a scalpel and tapped lightly on something white showing through the red granulating knuckle of my right fore-finger. “Bone,” he remarked laconically. He looked at the badly contracted eyelids and the rapidly forming keloids, and pursed his lips. “Four new eyelids, I’m afraid, but you are not ready for them yet. I want all this skin to soften up a lot first.

This time when the dressings were taken down I looked exactly like an orang-outang. McIndoe had pinched out two semicircular ledges of skin under my eyes to allow for contraction of the new lids. What was not absorbed was to be sliced off when I came in for my next operation, a new upper lip.

In 1941, Hillary persuaded the British authorities to send him to America to rally support for Britain’s war effort. While in the United States, he spoke on the radio, had a love affair with the actress Merle Oberon, and drafted much of The Last Enemy.[8]

Hillary managed to bluff his way back into a flying position even though, as was noted in the officers’ mess, he could barely handle a knife and fork. He returned to service with No 54 Operational Training Unit at RAF Charterhall after recovering from his injuries, for a conversion course to pilot light bomber aircraft.

Hillary was killed in his 24th year on 8 January 1943, along with Navigator/Radio Operator Sgt. Wilfred Fison, when he crashed a Bristol Blenheim during a night training flight in adverse weather conditions, the aircraft coming down on farmland in Berwickshire, Scotland.

Turned Towards the Sun can be rented on Amazon

Gallery of screenshots from the crowd-funded documentary filmed in the last year of Mick Burn’s life (which you can rent here)