CURTIS, Lettice (#77)

#77

Miss Lettice CURTIS MA MRAeS

Royal Air Force (Air Transport Auxiliary)

(1 February, 1915 - 21 July, 2014)

“the most remarkable woman pilot of the Second World War.”

Miss Lettice Curtis boarding a Spitfire in a colourised photograph released to mark the 100th Anniversary of the Royal Air Force. (To mark the 50th Anniversary of the Royal Air Force, Alan Pollock took a somewhat different approach).

Captain Pauline Gower of the Women’s Air Transport Auxiliary

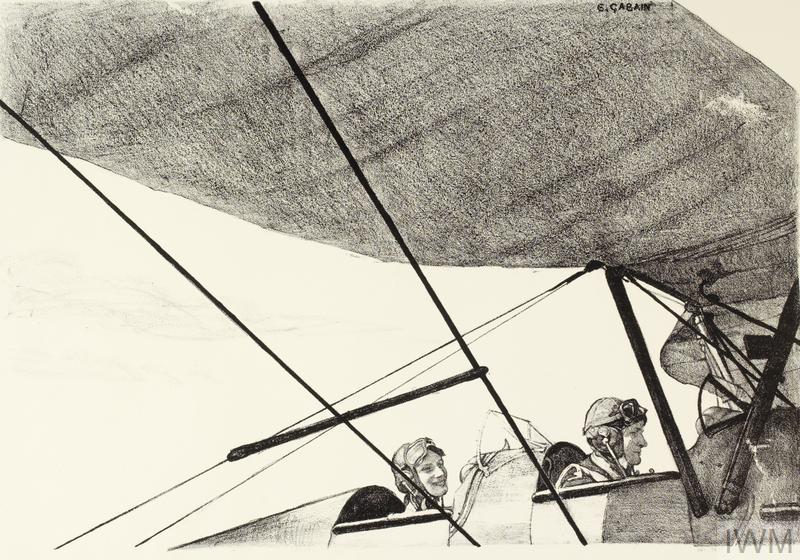

Women’s Work in the War (Other than the Services) – Six lithographs by Ethel Leontine Gabain (1941) Two members of the women’s branch of the Air Transport Auxiliary, the organisation which is responsible for flying aircraft between factories and Royal Air Force Stations, seated in a trainer. The experienced airwoman in the front seat is an instructor. She is taking up a less experienced recruit to this valuable organisation.’ (Historical caption, 1941). © IWM LD 1537.

Lettice Curtis boarding a Spitfire

‘Lettice Curtis was one of the first women to work for the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) as a pilot and was described in her Telegraph obituary as “arguably the most remarkable woman pilot of the Second World War.”

‘She joined the ATA in July 1940 and worked until the end of the war, when the ATA was disbanded. She had delivered over 1500 airplanes, including 222 Halifaxes and 109 Stirlings.

‘Her love of flying had been ignited by a chance encounter one day just before the war. She had struck up a conversation with a pilot at Haldon airfield in Devon one day and had, off the cuff, enquired whether women could also be pilots. Apparently, they could. A bequest from her grandmother of £100 enabled funded her training and, later that year, 1937, she got her licence at Yapton Flying Club, Ford, West Sussex.

‘She was invited to join the ATA by the daughter of a Conservative MP, Pauline Gower, organiser of the women’s section of the ATA. The idea of women flying planes had met with great resistance, best exemplified by the following quote: “The menace,” the editor of the Aeroplane, CG Grey, had written, “is the woman who thinks she ought to be flying a high-speed bomber when she really has not the intelligence to scrub the floor of a hospital properly.”

“Chocks Away: An ATA pilot readies herself for a mission.” Museum of Berkshire Aviation

‘And even when they had been allowed to fly planes, the male establishment tried to restrict the type of planes they could fly. “The men did not allow women to fly some new types right away,” wrote another ATA flyer, Diana Barnato Walker. “There was a lot of humming and hawing before Lettice Curtis, a tall, blue-eyed blond girl, an excellent pilot … was allowed to ferry a Typhoon on 24 June 1942.”

‘But the pressures of war, as in so much of the rest of society, soon caused the barriers to women’s participation collapse.

Ferry Pilots by Ethel Leontine Gabain (1941) © IWM LD 1533

‘Lettice revelled in the freedom flying gave her, away from petty-minded men on the ground. “The cockpit of the Tiger was my world. Control of it lay in my own hands, this was an entirely satisfactory state of affairs.”

‘Public recognition came in several forms, not least of which was when Lettice and other women ATA pilots were introduced to Clementine Churchill, wife of the Prime Minister, and Eleanor Roosevelt, the First Lady. The headlines proclaimed, “Mrs Roosevelt Meets Halifax Girl Pilot.”

‘And how she had impressed on her initial Halifax flight. The description of her historic solo flight in the ATA’s official book Brief Glory. The Story of A.T.A. (Aircraft Transport Auxiliary) describes how the wheels “kissed the surface gently and the 30-ton aircraft rolled steadily down the runway in the smooth manner which seldom characterises a first solo, and came to a dignified halt”, much to the surprise of the station master.

‘He reputedly turned to the General beside and commented: “It didn’t swing! It didn’t even bounce! And my lads have always kidded me how difficult Halifaxes are. Why, damn it, they must be easy if a little girl can fly them like that!”

‘After the war, Lettice again ran up against the familiar prejudices against her sex. Lettice, who had kept her commercial licence current and now had ten different types of public transport aircraft in her logbook, set out to find a job as a pilot. She wrote to all the airlines advertising for pilots. “For the most part they interviewed me, mostly, I felt out of curiosity, before thinking up a reason for not taking me on,” she wrote. Eventually, she was offered a job with the Ministry of Civil Aviation as an Operations Officer before applying to be a test pilot at the Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment at Boscombe Down.

‘After her flight test, she received a letter telling her they were “quite satisfied” that she would make a success of the job, given the combination of her flying and technical skills. However, it added that the official processes were now at work and it was for the Establishment’s people at the Ministry of Supply to make the official approach. “I am bound to tell you that they may hedge at employing a woman for, as you yourself realise, Government Departments do not like to set a precedent.” No precedent was set.” (Aero Society obituary)

‘She finally got a job as a flight-test observer, work that extended into tropical aircraft testing and an intercontinental mission, co-piloting a Lincoln bomber to the missile-testing station in Woomera, Australia. From 1953 into the 1960s she was employed, briefly, by Folland and then Fairey Aviation before joining the Civil Aviation Authority, where she stayed until 1976.

‘At the grand age of 77, she got her helicopter pilot’s licence.’ (Michael J Hawkins)

‘On Getting My Helicoper License’ 1992 by Lettice Curtis. ATA Museum

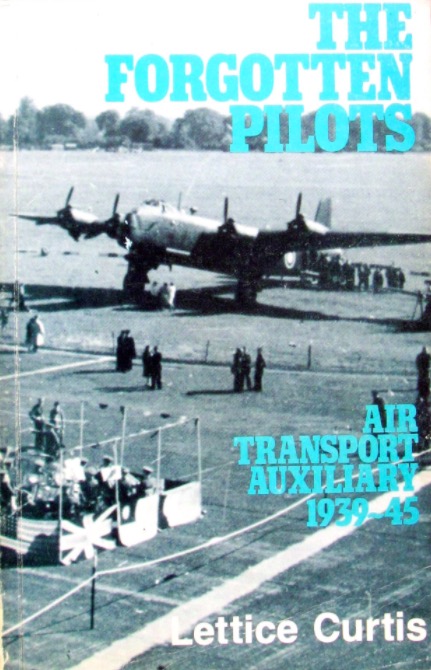

Forgotten Pilots: Story of the Air Transport Auxiliary, 1939-45 by Lettice Curtis. “Her book The Forgotten Pilots illustrates country’s debt to Lords Beaverbrook & Signatory No. 13: Lord Balfour), and AIR TRANSPORT AUXILIARY. (ARP note)”

“the Air Transport Auxiliary were civilians in uniforms who played a soldiers part in the Battle for Britain”

Lord Balfour, Under Secretary of State of Air (Signatory 13)

Videos:

‘The Forgotten Pilots: The fascinating inside story of the WW2 British Air Transport Auxillary (A.T.A.) featuring interviews with many of the surviving pilots. ITV West TV production from 2005. People interviewed include Lettice Curtis, Diana Barnato Walker, Freydis Sharland, Peter Mursell, Jackie Moggridge, Maureen De Popp, ‘Chile’, Philippa Booth, Maggie Frost, Johnny Jordan, Joy Lofthouse, Eric Viles, Don Hoare and Peter George & featuring a whole host of WW2 British and American aircraft.

Part 1a:

Part 1b

Part 2a

Part 2b

Lettice Curtis – obituary

‘Lettice Curtis was a pilot who ferried Spitfires to frontline squadrons and gained her helicopter licence at the age of 77

‘Lettice Curtis, who has died aged 99, was arguably the most remarkable woman pilot of the Second World War, flying a wide range of military combat aircraft with the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) and being the first woman to qualify to fly a four-engine bomber.

She had qualified as a commercial pilot in April 1938, and was working for the Ordnance Survey when, in June 1940, she was approached by the ATA. There was an urgent need for more pilots to ferry aircraft and, with most men joining the RAF, it was decided to form a Women’s Pool to bolster the number of pilots. Lettice Curtis was among the first to join .

With a small group of other young women, she began by flying light training and communications aircraft at Hatfield. She soon graduated to more advanced trainers and also the twin-engined Oxford. ATA pilots often flew alone and with no navigation aids — they had to rely almost entirely on map reading as they ferried aircraft from factories and airfields to RAF units around the United Kingdom. Weather conditions were often difficult.

Until the spring of 1941 there was a government ruling that women could not fly operational aircraft, but everything changed that summer. Without any extra tuition, and just a printed preflight checklist, Lettice Curtis ferried a Hurricane to Prestwick. Soon she was flying the fighter regularly, and it was not long before she was also delivering Spitfires to frontline squadrons.

In September 1941 the role of women pilots was extended further, and Lettice Curtis quickly graduated to the more advanced aircraft, ferrying light bombers such as the Blenheim and the Hampden. She then converted to the even more demanding Wellington, later observing: “Before flying [the Wellington] it was simply a question of reading Pilot’s Notes.”

At the end of September 1942, Lettice Curtis was sent to an RAF bomber airfield where she was trained to fly the Halifax. On October 27, Mrs Eleanor Roosevelt, accompanied by Mrs Clementine Churchill, visited the ATA to meet the women pilots. Lettice Curtis stood under the wing of a Halifax in the pouring rain and was introduced to the American President’s wife as the first woman to fly a four-engine bomber. The encounter prompted a field day in the national press, one headline reading: “Mrs Roosevelt meets Halifax girl pilot”.

In 1943 Lettice Curtis was authorised to ferry more types of heavy bombers, including the US B-17 Flying Fortress. The following year she was the first woman pilot to deliver a Lancaster. By the end of the war, when the ATA closed down, Lettice Curtis was probably the most experienced of all the female pilots, having flown more than 400 heavy bombers, 150 Mosquitos and hundreds of Hurricanes and Spitfires.

Eleanor Lettice Curtis was born at Denbury, Devon, on February 1 1915 and educated at Benenden School in Kent and St Hilda’s College, Oxford, where she read Mathematics and captained the women’s lawn tennis and fencing teams; she also represented the university at lacrosse, and was a county tennis and squash player.

She learned to fly at Yapton Flying Club near Chichester in the summer of 1937. After her initial training, she flew a further 100 hours solo in order to gain her commercial B licence. She did not expect to get a flying job, but in the event was taken on by CL Aerial Surveys, which she joined in May 1938.

Flying a Puss Moth fitted with a survey camera, she photographed areas of England for the Ordnance Survey. On the outbreak of war she transferred to the Ordnance Survey’s research department and nine months later she joined the ATA.

Post-war Lettice Curtis worked as a technician and flight test observer at the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment before becoming the senior flight development engineer with Fairey Aviation in 1953. She also flew as a test observer in the Royal Navy’s Gannet anti-submarine aircraft and regularly flew Fairey’s communication aircraft.

Her love of flying never diminished, and she regularly took part in the National Air Races organised by the Royal Aero Club, piloting a variety of competitive aircraft, among them a Spitfire belonging to the American civil air attaché in London. In this Spitfire she raced against the country’s top test pilots, and achieved a number of high placings. She later bought her own aircraft (a Wicko), in which she competed in a number of Daily Express Air Races.

In the early 1960s, Lettice Curtis left Fairey for the Ministry of Aviation, working for a number of years on the initial planning of the joint Military and Civil Air Traffic Control Centre at West Drayton. After a spell with the Flight Operations Inspectorate of the Civil Aviation Authority, in 1976 she took a job as an engineer with Sperry Aviation.

A strong supporter of Concorde (her Concorde Club number was 151)*, she made two flights in the famous airliner. In 1992 she gained her helicopter licence, but three years later decided that, at the age of 80, her flying days were over.

A strong-willed, determined individual, Lettice Curtis always felt that the ATA did not receive the recognition it deserved, and in 1971 she published The Forgotten Pilots. Her autobiography, Lettice Curtis, came out in 2004.

Lettice Curtis, who was unmarried, was in great demand on the lecture circuit and as a guest on RAF stations. She was one of the first patrons and supporters of the Yorkshire Air Museum.

Lettice Curtis, born February 1, 1915, died July 21, 2014′ Obituary courtesy of The Daily Telegraph

*Readers may be interested to know that all of the “They Were There” prints were flown on Concorde. Because Mach Speed 2.

_________

British Prime Minister Theresa May, alongside President Donald J. Trump talking with Queen Elizabeth II, as they and other D-Day Commemoration leaders gather for a group photo Tuesday, June 4, 2019, prior to the Commemoration Ceremony honoring the 75th anniversary of D-Day in Porstmouth. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)

Lettice Curtis would also have been the first guest at Theresa May’s ‘Dream Dinner Party’

From Edward Whymper to Agatha Christie: Who would be at Theresa May’s dream dinner party?’

‘The Telegraph asked Theresa May who would be at her dream dinner party, and here are her choices:

Lettice Curtis

Former constituent of Mrs May who was an aviator, flight test engineer and air racing pilot who, on the outbreak of WWII, became one of the first women pilots to join the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA).

Sir Stanley Spencer, Tea in the Hospital Ward, Sandham Memorial Chapel, Burghclere. © National Trust/John Hammond

Other guests included Sir Stanley Spencer, who created perhaps the greatest of Great War Memorials in the Sandham Memorial Chapel, and married Hilda Carline, sister of the Great War Artists Sydney and Richard Carline, some of whose work can be seen in Harold Balfour’s page on this site); Major Wilfred Thesiger (who won a DSO in WWII and served in the Special Operations Executive and Special Air Service); Gertrude Jekyll, who worked with Sir Edward Lutyens planning First World War Memorial Gardens; Edward Whymper and Agatha Christie).

High Flight by John Gillespie Magee Jr. (9 June 1922 – 11 December 1941)

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds, – and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of – wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there,

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air…

Up, up the long, delirious burning blue

I’ve topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark, or ever eagle flew –

And, while with silent, lifting mind I’ve trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

(Both photos via the excellent resource that is Aircrew Remembered)