‘Shot down 12.55 hrs. Baled out’

A laconic log-book entry that hardly begins to capture the actuality of James Nicolson’s sortie in a 249 Squadron Hurricane that Friday, August 16th, 1940.

Recalling the events, anonymously, in a radio broadcast later, he was more forthcoming:

Recalling the events, anonymously, in a radio broadcast later, he was more forthcoming:

The first shell tore through the hood over my cockpit and sent splinters into my left eye. One splinter I later discovered nearly severed my eyelid. I couldn’t see through that eye for blood. The second cannon shell struck my spare petrol tank and set it on fire. The third shell crashed into the cockpit and tore off my right trouser leg. The fourth shell struck the back of my left shoe. It shattered the heel of the shoe and made quite a mess of my left foot but I didn’t know anything about that until later. Anyway, the effect of these four shells was to make me dive away to the right to avoid further shells then I started cursing myself for my carelessness. “What a fool I’ve been”, I thought. “What a fool”…

By this time, it was pretty hot inside my machine from the burst petrol tank. I couldn’t see much flame but I reckoned it was there alright. I remember looking once at my left hand, which was keeping the throttle open, which seemed to be in the fire itself and I could see the skin peeling off it.

Nicolson had been hit by a Messerschmitt Bf 110, escorting three Junker Ju88s he’d had his eye on. The Battle of Britain Historical Society takes up the story:

He then got the 110 in his sights, he lined it up and with his finger rock hard on the firing button blasted away at the bandit, his badly injured hand taking all the pain that it could. Suddenly, the 110 was engulfed in smoke, and it then turned, went into a gentle dive and spiralled down into the sea below.

He tried desperately to disengage the harness from his body, and pulled a useless left leg up towards him, then dived head first out of the burning ball of flame that once was his Hurricane. It is said that he actually fell some 5,000 feet before realizing that he had to pull the ripcord. His left eye, now completely blinded with blood, his other eye closed as if it was a relief to rest them as he gently descended towards solid ground.

Once landed, he saw with his good eye, that blood was pouring through the lace holes of his left boot, his flying jacket showed signs of being burnt, and the glass on his wrist watch had melted.

Wing Commander J. B. Nicolson VC (1917-1945) by Frank Thatcher; Royal Air Force Museum

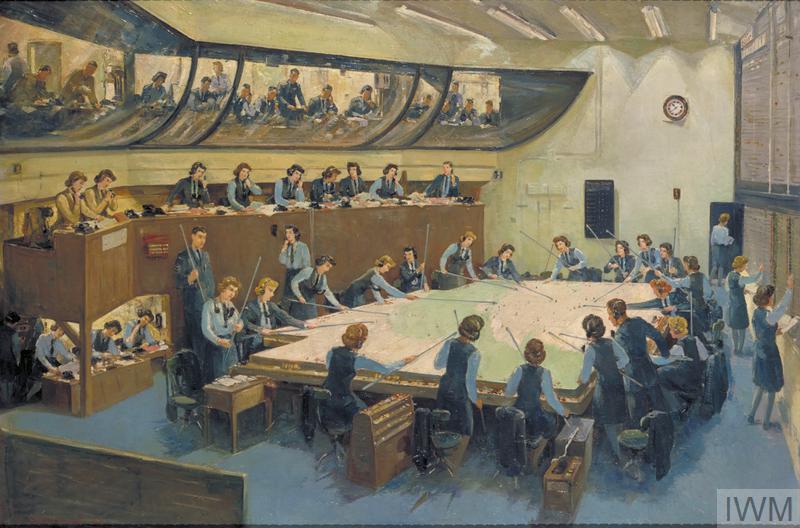

Just hours later, and three score miles away, Winston Churchill left RAF Uxbridge, where he’d been visiting the No 11 Group Operations Room, to monitor The Battle of Britain.

No 11 Fighter Group’s Operations Room, Uxbridge by Charles Ernest Cundall (1943) © IWM Art.IWM ART LD 4140

Turning to his chief military assistant, Major General Hastings ‘Pug’ Ismay, he said: “Don’t speak to me, I have never been so moved.”

After a long silence stretching several minutes, Churchill spoke again:

“Never in the history of mankind has so much been owed by so many to so few”.

(A few days later, on the way to the Commons, Churchill was rehearsing the line again for his famous speech when Ismay asked, “What about Jesus and the disciples?” Churchill replied, “Good old Pug” – and changed it to “never in the history of human conflict.”)

“The Few” © IWM PC 14972

Three months later Nicolson was awarded the Victoria Cross – the only one given in the war to a pilot from Fighter Command, and considered by many to also symbolically honour ‘The Few’ – that vital collection of fighter pilots and crews who had won the skies at such terrible cost.

© IWM 1695

Five years later Nicolson, flying as an observer over the Bay of Bengal, was reported as missing, presumed dead. He left a widow, Muriel, and a young son.

In 1983, aged 79, Muriel sold the VC for a then record sum – to help her survive. Her War Widows pension, as the surviving spouse of a VC, was just £44.

Muriel Nicolson in a screenshot from a Pathe newsreel (below): “We can hardly wait for my husband to come home…we’ve had so many messages and telegrams…here’s a good one… “Delighted to see your ugly mug on all the front pages for such a good reason.”

Alan Pollock, driving Muriel to the Inauguration of the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum, which he had been instrumental in helping to found, learned of this, and the War Widows Pension Campaign led by Iris Strange, and saw a way to help – using some of the signed prints he had donated to Tangmere to help raise funds. Others felt strongly, too, and gladly added their signatures.

Tangmere Military Aviation Museum original button badge c. 1980

In fairly short order the campaign was successful and substantial sums were allocated to the War Widows by the Government. The print project then extended to become ‘They Were There: Blood, Toil, Tears and Sweat’, a Commemorative Tribute to Allied Forces in Two World Wars, in turn designed to raise funds for the three armed services’ benevolent charities.

Display dedicated to James ‘Nick’ Nicholson VC at Tangmere Military Aviation Museum. The original ‘Battle of Britain VC’ painting (as in the signed prints) above Nicolson’s flying jacket when he was shot down and baled.

An interesting account from a (then 7 year old) witness, alongside a detailed discussion about several elements in the display, can be found on the Key.Aero Forum:

Sorry if I appear to be late on parade chaps, but, better late than never, as they say. I was witness to the Dogfight on the 16th. August 1940, from my bedroom window, at Eastleigh. The contrails were making lazy circles, in the cloudless sky, When,- out of the melee, i could see intermittent puffs of black smoke, coming down. –Then, there it was,a ‘plane’ passing by the tall pines at the front of the copse, about half a mile away, coming down, at a 30% angle. Guessing the spot where it would land, I wasted little time in getting my 7 year old legs in gear. As the siren had not sounded, it was OK to go out. I was the first of a few other boys to see this 109,with the number 13 on its side, sitting on the grass, wheels up. Walking around it, i spotted a piece, hanging down from the wing, and on giving it a bit of a waggle, it came away in my hand. It was what I know now to have been the ‘Starboard aileron balance weight strut’. minus the lead, that had snagged the cattle fence, at Leigh Road. Sadly, I do not have it now.

I was to learn much later, that was removed to ‘Cunliffe Owens’ at Eastleigh, were it was repaired and flown for evaluation purposes.

Alfred W Thorne.

R.A.F. FIGHTER V.C. Original wartime caption: ‘The Swanee whistle.’ Nicolson (centre) while recovering in hospital. Copyright: © IWM CH 1696

“I remember looking once at my left hand, which was keeping the throttle open, which seemed to be in the fire itself”

From Nicolson’s (then) anonymous radio talk about his action, broadcast in December 1940:

That was a glorious day. The sun was shining from a cloudless sky, with hardly a breath of wind anywhere. My squadron was going towards Southampton on patrol at 15,000 feet when I saw three Ju 88 bombers about four miles away, flying across our bows.

I reported this to our squadron leader and he replied, ‘Go after them with your section’. So I led my section round and towards the bombers. We chased hard after them but when we were about a mile behind we saw the 88s fly straight into a squadron of Spitfires. I used to fly a Spitfire myself and I guessed it was curtains for the three Junkers. I was right and they were all shot down in quick time with no pickings for us. I must confess I was very disappointed for I had never fired at a Hun in my life and I was dying to have a crack at them.

So we swung round again and started to climb up to 18,000 feet over Southampton to re-join our squadron. I was still a long way from the squadron when suddenly, very close in rapid succession, I heard four big bangs. They were the loudest noises I had ever heard and they had been made by four cannon shells from a Messerschmitt 110 hitting my machine.

The first shell tore through the hood over my cockpit and sent splinters into my left eye. One splinter I later discovered nearly severed my eyelid. I couldn’t see through that eye for blood. The second cannon shell struck my spare petrol tank and set it on fire. The third shell crashed into the cockpit and tore off my right trouser leg. The fourth shell struck the back of my left shoe. It shattered the heel of the shoe and made quite a mess of my left foot but I didn’t know anything about that until later. Anyway, the effect of these four shells was to make me dive away to the right to avoid further shells then I started cursing myself for my carelessness. “What a fool I’ve been”, I thought. “What a fool”.

I was just thinking about jumping out when suddenly a Messerschmitt 110 whizzed underneath me and got right in my gun sight. Fortunately no damage had been done to my windscreen or sights and when I was chasing the Junkers I had switched everything on, so everything was set to for a fight. I pressed the gun button for the Messerschmitt was in nice range.

He was going like mad twisting and turning as he tried to get away from my fire so I pushed the throttle wide open. We went down together in a dive. First he turned left then right, then left and right again. He did three turns to the right and finally a fourth turn to the left. I remember shouting out loud at him when I first saw him ‘I’ll teach you some manners you Hun’, and I shouted other things as well. I knew I was getting him nearly all the time I was firing.

I gave him a parting burst and as he disappeared I started thinking about saving myself.

By this time it was pretty hot inside my machine from the burst petrol tank. I couldn’t see much flame but I reckoned it was there alright. I remember looking once at my left hand, which was keeping the throttle open, which seemed to be in the fire itself and I could see the skin peeling off it, yet I had little pain. Unconsciously too, I had drawn my feet up under my parachute on the seat, to escape the heat, I suppose.

Well, I gave the Hun all I had and the last I saw of him, he was going down with his right wing lower than his left wing.’

249 Squadron’s mascots: Pipsqueak (dog, left) and Wilfred (duck, right)

via Britain At War

Imperial War Museum Oral History by Eric James Brindlay Nicolson VC

Wing Commander James Brindley ‘Nick’ Nicolson VC DFC

British officer served as pilot with 249 Sqdn, RAF account of bailing out after action for which he was awarded Victoria Cross during Battle of Britain, 16/8/1940